Meeting Cost Calculator

Calculate meeting costs with this interactive meeting cost calculator giving you an accurate representation of how much money your meetings are...

Learn how to calculate the cost of meetings per employee and discover strategies to reduce unnecessary meeting expenses in your organization.

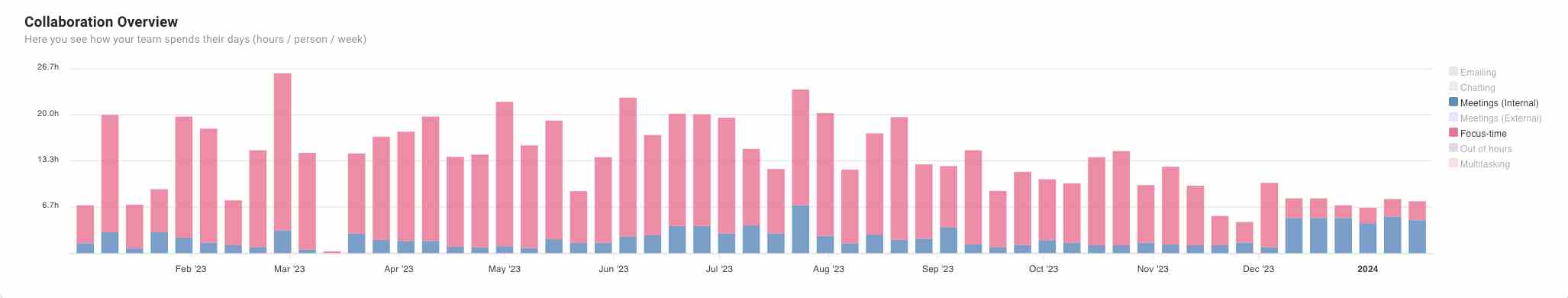

Meeting time is easy to notice and hard to quantify, which is exactly why it becomes one of the most expensive forms of organisational drift: calendars fill up slowly, recurring meetings become “how work happens,” and teams start confusing coordination with progress because everyone is busy but fewer things ship.

The cost of meetings per employee gives you a practical way to turn that drift into a number that leaders can understand and act on, because it translates meeting hours into financial cost, makes patterns comparable across teams, and creates a baseline you can use to judge whether changes in meeting culture are actually creating capacity.

When people say “meeting cost,” they often mean different things, so it helps to define the three most useful levels clearly before doing any calculations.

Meeting cost is the cost of a single meeting, which is determined by how long the meeting runs and the combined cost of everyone who attends it, meaning that two meetings with the same duration can have completely different price tags depending on seniority and headcount.

Cost of meetings for a company is the total cost of all meetings over a defined period (typically a month or a quarter), which is useful for communicating scale, budgeting opportunity cost, and spotting whether meeting load is rising faster than headcount.

Meeting cost per employee is the company meeting cost divided by headcount for the same period, which makes it easier to compare meeting intensity across functions, identify where coordination is becoming a hidden tax, and track whether changes are reducing meeting burden in a measurable way.

A credible calculation does not require perfect data, but it does require a method that is consistent, explicit about what is included, and easy to explain without qualification.

At its simplest, meeting cost is the sum of attendee costs for the time spent in the meeting:

This works best when hourly cost reflects the reality that an employee hour is more than salary, because salary alone underestimates the real cost of time spent in meetings and makes the number easier to dismiss.

A fully loaded hourly cost typically includes salary plus benefits, employer taxes, and overhead allocations, translated into a workable hourly figure, and while the exact approach varies by company, the key is that it should be consistent enough that trendlines mean something even if the first version uses approximations.

Once meeting cost is calculable at the meeting level, the company roll-up becomes straightforward:

This is the point where the metric becomes useful for leaders, because “meeting cost per employee per month” is easy to compare across teams, easy to track after interventions, and easy to connect back to calendar behaviour.

Here's some examples:

This is the simplest case, and it already shows why “just one hour” often becomes expensive when attendance grows.

Now take a realistic cross-functional meeting where seniority mix drives most of the cost, even when duration stays the same.

Cost calculation:

This is why meeting economics are not just about “how many meetings,” because the same meeting frequency becomes far more expensive when the default invite list includes higher-cost roles.

To convert meeting cost into a per-employee metric, you roll up meeting costs across the month and divide by headcount, which is what makes it possible to compare teams and track improvement.

This number becomes even more informative when you segment it by function or role band, because you can quickly see whether meeting load is concentrated in a small part of the organisation or spread broadly.

Meeting cost becomes far more useful when the scope is clear, because the moment scope is ambiguous, teams spend their energy debating definitions instead of improving outcomes.

For most organisations, it is practical to calculate internal meeting cost first, because internal meetings are where coordination patterns either create capacity or consume it, while external meetings (sales calls, customer support, partnerships) often have a different value model and can distort the headline number if they are blended together too early.

Recurring meetings deserve special attention because they behave like fixed overhead, meaning they continue regardless of whether the underlying need still exists, and because small recurring meetings are often responsible for a disproportionate share of total meeting cost when you aggregate them across weeks and months.

All-hands, onboarding, training, and structured team rituals can be expensive, but their purpose is often cultural or enablement-based rather than operational coordination, so it is usually clearer to report them as separate categories rather than mixing them into the same total that you want to use for efficiency decisions.

If you only account for scheduled time, you capture the visible cost but miss the mechanics that make meeting-heavy environments feel slow, because the damage often comes from what meetings do to execution rather than from the meeting blocks themselves.

The hidden cost that shows up most consistently is the recovery time required to return to focused work, especially when meetings are scattered across the day, because each interruption forces people to re-orient, rebuild context, and restart work that benefits from sustained attention, which is why calendar fragmentation can reduce output even when total meeting hours are not extreme.

Meeting-heavy organisations often become calendar-dependent for decisions, which means work waits for a scheduled moment of synchronisation rather than moving forward asynchronously, and this increases the volume of follow-ups, escalations, and “alignment” meetings that exist primarily because decisions were delayed rather than because collaboration was truly required.

McKinsey reports that 61% of executives say at least half the time they spend making decisions is ineffective, which helps explain why meeting volume grows when decision-making becomes slow or unclear.

Meetings rarely end when the invite ends, because unclear outcomes create follow-up threads, extra clarification calls, and additional coordination time, and when a team’s meeting system is weak, that spillover work can become a parallel workload that never appears in calendar analytics despite being directly caused by meetings.

When teams struggle to find reliable information, meetings become a default discovery mechanism, which feels productive in the moment but increases cost because information retrieval becomes synchronous and repetitive rather than accessible and reusable.

Gartner found that 47% of digital workers struggle to find the information needed to perform their jobs effectively, which is one reason meetings become the “place where we learn what’s going on” instead of a tool used selectively.

Meeting cost per employee does not rise only because people have more meetings, because it also rises when meetings take on shapes that make them more expensive, more frequent, and more disruptive to execution.

When decision rights are unclear or trust in information flow is low, meetings become more inclusive than necessary, and the organisation pays for that ambiguity through attendee count, because each additional attendee increases cost immediately while often contributing less value than the decision-makers and required inputs.

Recurring meetings that never re-justify themselves tend to survive as organisational habit, and because they are predictable they feel harmless, but they function as permanent overhead that accumulates across teams, which is why reducing the number of low-value recurring meetings is often the fastest path to lowering meeting cost per employee without disrupting essential collaboration.

A day filled with short, scattered meetings can be more damaging than a day with fewer, longer blocks, because scattered meetings prevent meaningful execution windows, increase context switching, and push deep work into evenings or into the schedules of the few people who are not booked solid, which effectively concentrates output onto a smaller part of the organisation.

When teams lack an easy way to see what is happening, what is blocked, and who owns the next step, status meetings become the substitute system, and the cost grows because the same information gets repeated weekly rather than stored in a way that makes it accessible without synchronous time.

Meeting cost reduction works best when it targets the patterns that create the most waste while preserving the meetings that actually prevent rework, resolve ambiguity, and move decisions forward, because cutting meetings indiscriminately often causes coordination to reappear elsewhere in less structured and more expensive ways.

Recurring status meetings are usually reducible when teams adopt a consistent asynchronous update format that makes progress visible without requiring everyone to be present at the same time, because the real need is shared context, not shared time, and once context becomes easy to consume, many “keep everyone aligned” meetings shrink or disappear naturally.

Attendance drops without drama when teams separate the people required to make the decision from the people who benefit from visibility, because observers can receive outcomes and notes while the decision group keeps the meeting small enough to move quickly and leave with clear ownership.

Meetings run long when they are designed around discussion rather than outcomes, so shortening meetings tends to be easier when the meeting has a clear end state (a decision, a shortlist, a plan, an owner with a deadline) and when pre-work is used to prevent the first half of the meeting from becoming a shared reading session.

Late starts and overruns are expensive because they cascade into the rest of the day, increase fragmentation, and create additional recovery time between meetings, which means fixing punctuality and timeboxing is not simply a “culture” improvement but a direct lever on meeting cost per employee.

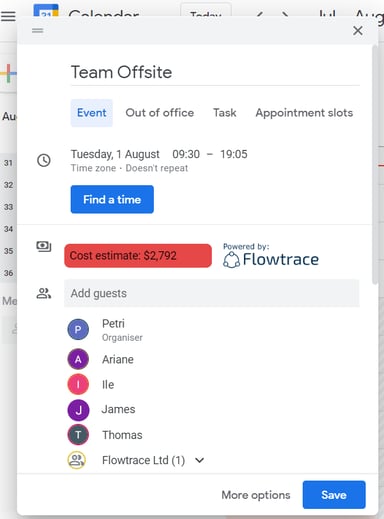

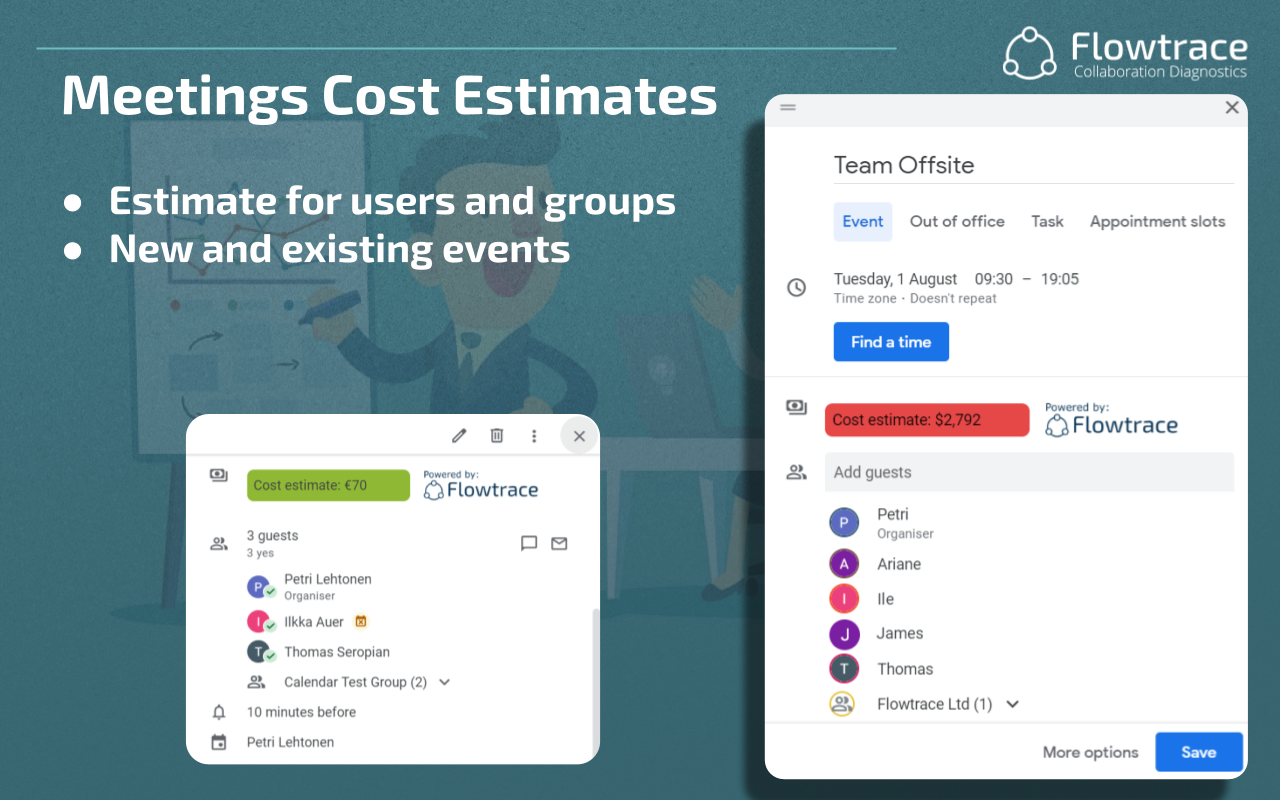

Meeting cost per employee only becomes operational when cost visibility shows up where decisions are actually made, which is inside the calendar invite while the meeting is being created or edited, because that is the moment an organiser can tighten the attendee list, shorten duration, add an agenda, or rethink whether the meeting should exist at all, instead of discovering weeks later that the month’s meeting spend has drifted upward with no clear lever to pull.

Flowtrace’s Google Calendar extension and Outlook add-in are built around that principle, bringing real-time meeting cost transparency directly into the tools people already use to schedule work, while pairing the cost view with invite governance so the meeting is evaluated against company scheduling rules and effectiveness policies before it becomes another recurring block everyone learns to live with.

In practice, this means organisers can see the estimated cost of a meeting as they plan it, and teams can apply consistent standards without relying on after-the-fact audits or spreadsheet exercises that only a few people can maintain, because the cost awareness and validation happens in the flow of scheduling across Google Calendar and Outlook (desktop and web) rather than in a separate reporting workflow that gets ignored when things get busy.

Flowtrace also supports centrally managed configuration, including role-based rates, so the cost numbers are consistent across teams and time periods, which is what allows companies to move from vague concern (“meetings feel expensive”) to a measurable view of where spend concentrates, which meeting series are repeatedly driving it, and what changes to invites and meeting structure will reduce it without breaking coordination.

The point of calculating meeting cost per employee is not to treat meetings as inherently bad, because many meetings prevent rework, align teams at the right moments, and reduce the risk of expensive misalignment, but when meeting time becomes the default response to uncertainty, the organisation starts paying a coordination bill that grows quietly and compounds over time.

When meeting cost becomes visible at the employee level, it becomes much easier to make decisions that protect execution time without harming collaboration, because the organisation can finally see which meetings are paying their way and which meetings are simply expensive habits.

Meeting cost per employee is the total internal meeting cost over a defined period (usually monthly or quarterly) divided by headcount, so you can understand how much meeting time is costing the organisation on a per-person basis rather than only seeing a large company-wide total that is hard to act on.

You calculate each meeting’s cost by multiplying meeting duration by the summed hourly cost of all attendees, then you add those meeting costs across the period and divide by headcount; in formula terms, meeting cost = duration × Σ(attendee hourly cost) and meeting cost per employee = total meeting cost ÷ headcount.

The most defensible approach is a fully loaded hourly cost (salary plus benefits, employer taxes, and overhead converted to an hourly figure), and if you do not have exact loaded rates per person you can use role bands (IC, manager, director, exec) so meetings with higher-cost attendees are reflected accurately rather than being averaged into a single number.

Most companies start with internal coordination meetings (status, planning, decision-making, alignment, recurring team meetings) because that’s where meeting overload usually hides, while separating external meetings (sales, customer calls) and enablement categories (training, onboarding, all-hands) into their own buckets so the metric stays useful for operational decisions instead of becoming a debate about scope.

Because the visible meeting time often triggers additional hidden costs—context switching and recovery time, decision delays that create extra alignment meetings, and spillover follow-ups when meetings end without clear decisions or ownership—so two teams with similar meeting hours can have very different real costs depending on calendar fragmentation, meeting size, and how often meetings create extra coordination work afterward.

Calculate meeting costs with this interactive meeting cost calculator giving you an accurate representation of how much money your meetings are...

Learn how to identify and measure wasted meeting time to boost productivity with a data-driven approach. Discover actionable insights for better...

Optimize meeting productivity with visual analytics for meeting data. Transform raw data into actionable insights, streamline meetings, and enhance...